The building known as 3614 Jackson Highway isn’t much to look at, inside or out. Squat and square, the concrete block structure has all the charm of a coffin showroom — which, in fact, it was back in the day, before the guys with guitars showed up.

Then again, “… and this is the bathroom where Keith Richards finished writing ‘Wild Horses,’” says my guide.

Well, that gets my attention. I’m standing at the open door of a tiny powder room just off this bare-bones recording studio in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. I peer inside at the loo, picturing Mick Jagger, Mick Taylor, Bill Wyman, and Charlie Watts hanging around, smoking and drinking and waiting for their comrade to emerge with the perfect riff to complete a rock’n’roll masterpiece.

What brought these superstars to a little town 130 miles south of Nashville and a universe away from London, L.A., or New York? The music, plain and simple.

For years, Muscle Shoals had already been attracting a galaxy of recording legends — from Wilson Pickett and Little Richard to Paul Anka, Duane Allman, Steven Tyler, and Aretha Franklin — who came here to work with its famous session band, the Swampers, and soak up a bit of that backwoods vibe.

This sleepy town by the Tennessee River is just the first stop in an epic — but surprisingly compact — 350-mile drive that embraces not only rock’n’roll, but the entire history of American popular music: gospel, soul, jazz, country, rock. You can make the trek in as little as three days, or stretch it out to a week or so. All you need is love (of music) — and a stop-by-stop playlist of America’s Greatest Hits.

Muscle Shoals, Alabama

PLAYLIST

- “Sweet Home Alabama,” Lynyrd Skynyrd

- “I’ll Take You There,” The Staple Singers

- “Tell Mama,” Etta James

- “Loves Me Like a Rock,” Paul Simon

It’s just a short drive to Muscle Shoals from the pleasingly compact Huntsville International Airport, with nonstop service from much of the country. The town had its beginnings as a recording center in the late 1950s, when an enterprising local fiddler named Rick Hall opened FAME Recording Studios above a drug store in nearby Florence. By 1963 he’d built a small recording studio in Muscle Shoals — the first of two studios I’ll be visiting today; a pair of landmarks that, over two decades, put Muscle Shoals on the world’s music map. I’m sitting in Rick Hall’s cluttered office, up a narrow stairway from the modest reception area, preserved in the exact condition it was when the Grammy-nominated producer died in 2018. On the walls hangs a gallery of gold records and photos of artists who stepped up to the microphones in the studio downstairs.

There’s just so much rock’n’roll history here. Within these four walls, Etta James recorded “Tell Mama,” Wilson Pickett introduced “Mustang Sally,” Percy Sledge first recorded “When a Man Loves a Woman,” and Jerry Reed wailed that “She Got the Goldmine (I Got the Shaft).”

Recording Studios is Aretha Franklin’s piano. (Photo by Bill Newcott)

Visitors can tour the studio — where, in but one more example, Aretha Franklin recorded her first hit record — every day but Sunday. (Go to famestudios.com/tour for details.) Muscle Shoals was more than a recording environment — it was the birthplace of a unique sound, nurtured by Hall and embodied in its studio musicians, the Swampers, who fused funk, rock, and country into what became known as the Muscle Shoals Sound. (The Swampers would later be immortalized in Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama.”)

“The Muscle Shoals Sound is a lot of things, and it’s hard to describe,” says David Hood, bass player and sole surviving Swamper. “Funk was at the root of it, especially in the early years. The sound often combines rock, soul, funk, and blues.”

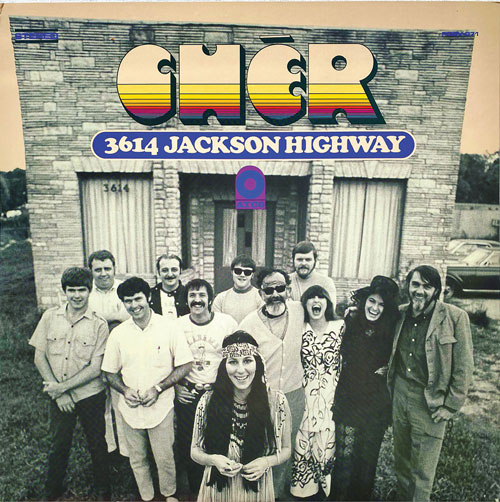

In 1969, the Swampers struck out on their own, leaving FAME Studios to start their own recording company a few miles away. Its official name was The Muscle Shoals Sound Studio, but that first year, Cher recorded a solo album there, called it 3614 Jackson Highway, and that became its unofficial name.

As you tour 3614 Jackson Highway, you can still see the corner where Hood sat playing his bass for the Staple Singers, creating what many call the most distinctive bass line of all time for their song “I’ll Take You There.” In fact, if you listen carefully to the recording, you’ll hear Mavis Staples calling out Hood’s name, urging him on.

“It was a magical session in so many ways,” Hood tells me over dinner at the 360 Grille, atop the Marriott Shoals Hotel and Spa, as I watch the setting sun turn the winding Tennessee River into a ribbon of red.

Leiper’s Fork, Tennessee

PLAYLIST

- “Tennessee Whiskey,” Chris Stapleton

- “Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around,” Carrie Underwood and Keith Urban

- “Leipers Fork,” Christopher Robin Band

Two hours north, along rolling hills via U.S. 43, I pull into the little town of Leiper’s Fork, Tennessee. It’s mid-afternoon when I arrive and wander into Creekside Trading, an arts, odds, and ends shop in the sleepy downtown. I can’t help but notice, hanging near the front door, several very nice-looking guitars.

“They’re not for sale,” I’m told by a staffer. “They’re for playing.”

You’d be hard-pressed to enter any Leiper’s Fork establishment without spotting guitars for the playing hanging on the walls. They’ve been put there by Aubrey Preston, a Nashville developer who’s made Leiper’s Fork his home — and pet preservation project.

“You see that picture of Hank Williams up there?” Preston asks me. We’re having a fried egg sandwich breakfast at Leiper’s Fork Farmer’s Market, which is lined with vintage guitars. “He’s playing a 1949 Southern Jumbo Gibson guitar,” he says. And I can’t help but notice that right next to the photo is a nearly identical instrument. “So, anyone can walk in here, pick up this guitar, and play it. It’s vintage, 1944, and very, very valuable.”

And just like that, Preston has taken the thing down and is picking away on it.

“A little outta tune,” he says, “but I don’t suppose there’s another store in the world where you can walk in and pick up one of these things.”

He gestures to a photo farther down the wall. “That’s Leonard Cohen before he was famous,” he says. According to local lore, Preston says, Cohen lived in a cabin with a fellow named Willie York, who did 20 years in prison for killing a constable.

The evening belongs to Fox & Locke, a historic grocery store that since 2002 has been featuring live music. Sitting in mismatched chairs and noshing on pork rinds, fried pickles, and the ever-popular “meat and three,” locals and visitors alike cram into Fox & Locke to hear upcoming hopefuls — along with Nashville royalty like Carrie Underwood and John Hiatt, dropping by to try out new material.

Nashville, Part 1

PLAYLIST

- “Better Day a-Comin’,” Michel LaRue

- “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” The Fisk Jubilee Singers

- “Strange Things Are Happening Every Day,” Sister Rosetta Tharpe

- “Oh Happy Day,” The Edwin Hawkins Singers

It’s about 25 miles from the sleepy streets of Leiper’s Fork to the big-city hubbub of Nashville. The drive along Route 46, through the heart of Williamson County, traces an old country road that once carried tobacco wagons to market. If you’d traveled this course in a horse-drawn carriage 200 years ago, you might have heard the songs of enslaved people floating over the low hills, songs of pain and defiance often wrapped in the imagery of faith and African tradition.

keep alive the tradition of the Negro spiritual around the world. (James Wallace Black/Library of Congress)

Elsewhere on the continent, European operas were being performed in the cities; Old Country-derived folk songs were being sung in the hills and hollows; drums, flutes, and vocal chants were echoing through Native American settlements. But here, in these farm fields and beyond, the seeds of a new, uniquely American music were being sown.

Looming over busy Broadway in downtown Nashville is a Digital Age institution devoted to preserving the decidedly analog legacy of those enslaved people and their descendants: the new National Museum of African American Music.

Divided into six galleries, the museum traces the development of what would become known as American Popular Music from its roots in African villages to spirituals to jazz to rock’n’roll to hip-hop.

The exhibit halls throb with videos and historic photographs, and as I move from gallery to gallery, centuries of music fade in and out.

I step into a glassed-in room. A digital choirmaster invites me to don a pink robe and join a gospel choir, projected onto a large wall, in a rendition of Edwin Hawkins’s “Oh Happy Day!” And there I am, projected on the wall with my new swaying, singing, virtual friends, doing my best to keep up. It’s pretty humbling — especially when I remember the folks behind me, looking through that big glass window.

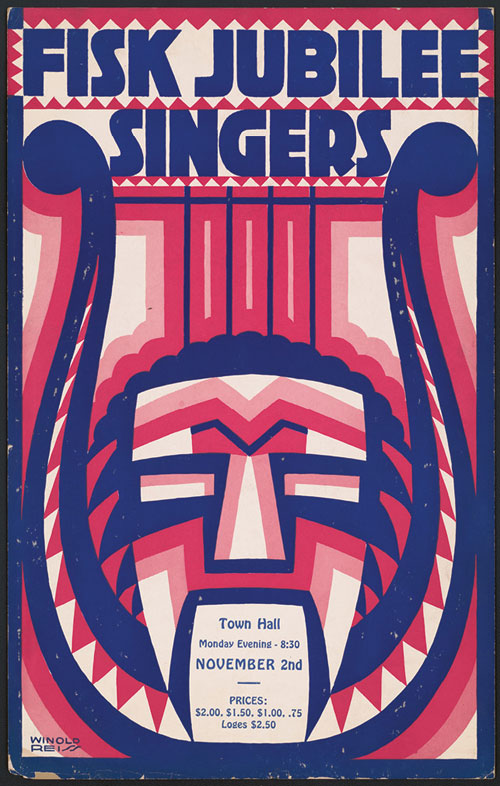

A hush falls over Ryman Auditorium, Nashville’s “Mother Church of Country Music.” On the same stage where Hank Williams wailed, “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” and Patsy Cline wondered if she might be crazy, nine young African American singers enter from the wings, their voices blending in a mesmerizing, almost whispering, rendition of the timeless slave song “Steal Away.”

“The trumpet sounds within my soul,” they sing, and you can almost hear that horn, muted and mournful. “I ain’t got long to stay here.”

On this night, the Fisk Jubilee Singers — founded more than 150 years ago to raise money for one of the South’s oldest historically Black universities — have seized hold of 2,000 hearts and, almost instantaneously, squeezed them to the point of tears. Just 5 minutes from downtown Nashville, Fisk University — founded to educate formerly enslaved people — owes its existence to the singers, whose late-19th-century national tours saved the school from financial ruin. For tens of thousands of post-Civil War white Americans, before the Fisk Jubilee Singers, the only Black performers they’d ever seen were in minstrel shows.

If you’re lucky enough to be in town for a Jubilee Singers concert, just go. And if you’re not, at least drop by the campus and wander through the singers’ rehearsal hall, dominated by a painting of the earliest iteration, visiting London, bringing Black music, for the first time, back across the Atlantic.

Nashville, Part 2

PLAYLIST

- “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” Hank Williams

- “You Don’t Know Me,” Ray Charles

- “Don’t Come Home a Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ on Your Mind),” Loretta Lynn

- “He Stopped Loving Her Today,” George Jones

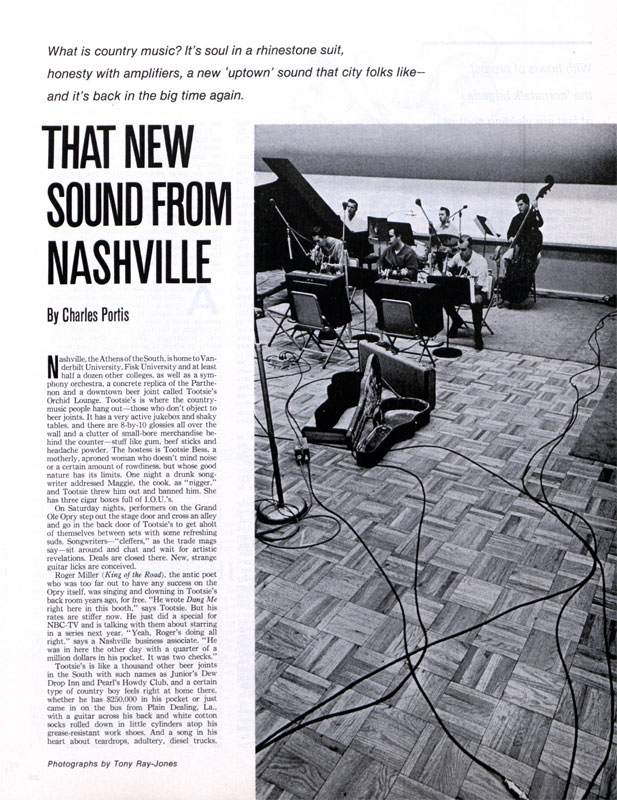

They say Queen Victoria, upon hearing the Fisk Jubilee singers, gushed, “You must come from a very musical city.” And that, those same people also say, is the genesis of Nashville’s adopted moniker, Music City. Indeed, music is inescapable here. Walk along Broadway, day or night, and a cacophony of music — battling bands of country and rock — spills through the honky-tonk doors and onto the sidewalk.

The scope of Nashville’s music scene comes into sharp focus at the Musicians Hall of Fame, another high-tech museum, tucked beneath the venerable Nashville Municipal Auditorium.

Besides a trove of musical relics — Elvis’s 1966 Fender Electric, a drum kit from Woodstock, JFK’s portable record player — the museum features lots of hands-on activities, including an opportunity to back up Ray Charles as one of his Raelettes. I try standing in line for a turn, but the kids in front of me are having way too much fun singing “Hit the Road, Jack” with Brother Ray. It’s best just to listen.

Of course, it seems that every street and alleyway in Nashville leads to Ryman Auditorium. Built as a church, it was home to the Grand Ole Opry for more than 30 years until 1974, when the show moved to a massive theater a few miles away. Still, there are top-name concerts here nearly every night — and if you take the tour, they’ll let you stand behind an iconic microphone for a picture. Maybe you’ll have the guts to belt out a few bars of Hank Williams’s “Hey, Good Lookin.” I do not.

On Nashville’s Broadway, it seems every night is New Year’s Eve. As I elbow my way through the mob, my ears trying in vain to discern which deafening melodic line is emanating from Lucky Bastard Saloon and which one is blasting from Nudie’s Honky Tonk, Nashville seems less a 24-hour music venue to me than a nonstop party.

Ears ringing, I head back toward my hotel (The Bobby, a funky and fun place with a full-size vintage Greyhound bus on the roof) and wander up a quiet side street, identified by a lit sign as “Printers Alley.”

Here, where newspapers were printed in the 1910s, a stubbornly subdued jazz culture persists. In decades past, after a day of twanging electric guitars for country music records, the likes of Chet Atkins and Floyd Cramer used to drop by here, mellowing out to the music of jazz combos — and sometimes jamming with them.

Today — besides a few long-established strip clubs — you’ll find upscale jazz at Skull’s Rainbow Room and classic British rock at Fleet Street Pub. What you won’t find is the clamor and clatter of Broadway.

Brownsville, Tennessee

PLAYLIST

- “Too Many Ties That Bind,” Tina Turner

- “Proud Mary,” Ike and Tina Turner

- “What’s Love Got to Do with It,” Tina Turner

If things are slow at the West Tennessee Delta Heritage Museum, Sonia Outlaw-Clark, the museum’s executive director, might come out to the parking lot to greet you.

“Come on in! I’ve just made coffee!” she enthuses, and I can confidently say I’ve never before felt so welcome at a museum.

Just off Interstate 40 between Nashville and Memphis — past wonderfully named towns like Sugar Tree and Bucksnort — the museum is a compact collection of local history.

On this day, Outlaw-Clark is thrilled to show me around the two buildings next door, both moved to this spot several years ago. One, a ramshackle shotgun shack with falling plaster and a tin-roof porch, was the home of storied blues singer Sleepy John Estes, who regularly toured Europe in the 1960s but always came home to his splendid squalor in Brownsville.

The larger building is the Flagg Grove School, a modest, one-room country schoolhouse, unremarkable save one fact: One of the school’s rustic, secondhand desks was for eight years occupied by a little girl named Anna Mae Bullock. You know her as Tina Turner.

Inside, Turner’s hits play over a speaker system, and encased in glass are some of her more outlandish outfits, including that funky costume from Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome.

Back in the main museum, I can’t help but notice a collection of guitars set up at one end of the lobby. And empty chairs.

“Oh, yes,” Outlaw-Clark says. “Those are there for anybody to play if they like.”

“I think I know who gave those to you,” I say.

“Oh, do you know Aubrey?”

Tennessee is a small state.

Memphis

PLAYLIST

- “She’s a Mean Job Blues,” W.C. Handy’s Memphis Blues Band

- “Beale Street Blues,” Louis Armstrong

- “Woke Up This Morning (My Baby Was Gone),” B.B. King

- “That’s All Right,” Elvis Presley

There are ghosts on Beale Street, the storied avenue that runs through downtown Memphis and pours itself into the Mississippi River. It was here that, in 1909, a young musician named W.C. Handy came to town with his Knights of Pythias band. For Black musicians, the speakeasies and clubs of Beale Street became not just a fertile job market, but an artistic destination. Louis Armstrong, revolutionizing jazz with his trumpet and scat singing, played behind these storefronts. So did Muddy Waters and Rosco Gordon and B.B. King.

It was King who struck up a friendship with a young Memphis white boy, a blue-eyed, pompadoured kid named Elvis Presley. The pair immersed themselves in Memphis blues, playing long into the night. Together, they were lighting the fuse on an artistic bomb that would explode around the globe.

Through pure, primeval genius, Elvis Presley would fuse centuries of African music tradition with the sputtering urgency of three-chord, milky-white rock’n’roll. Never, not for one second, did Elvis fail to acknowledge his debt to the ghosts of Beale Street.

“Hey! C’mere! I wanna ask you something!”

I’m outside Memphis’s Stax Museum of American Soul Music — a collection bristling with mementos of the record label’s eventful history, including records by Otis Redding and Isaac Hayes (whose gold-plated Cadillac is on proud display) — and now I’m being summoned by this guy about to climb into a car parked out front.

Now, I’ve been around long enough to know that when some stranger calls to you on a city street and says, “C’mere,” there’s only one rule: Smile, nod, and back away.

“No!” He insists with a crooked smile. “Come here!”

Well, okay. Rules are made to be broken. I round the trunk to the street side of the car. The fellow extends his hand.

“I just figured you might want to shake my hand!” he laughs. “You know who I am?”

I’m still using that getaway smile I plastered on a few seconds ago. I shake my head.

“Man, I am David Porter!” he laughs. “And I just wanted to say hey.” He jumps into his Tesla, and he’s gone.

This is what smartphones are made for. I’m only halfway through typing his last name when the screen explodes with Wikipedia knowledge about David Porter: Songwriters Hall of Fame … 1,700 songwriter and composer credits for a wide range of artists, including Aretha Franklin, James Brown, Ted Nugent, Patsy Cline, and the Eurythmics.

I glance at the car, now disappearing down McLemore Avenue. He was right. I did want to shake his hand.

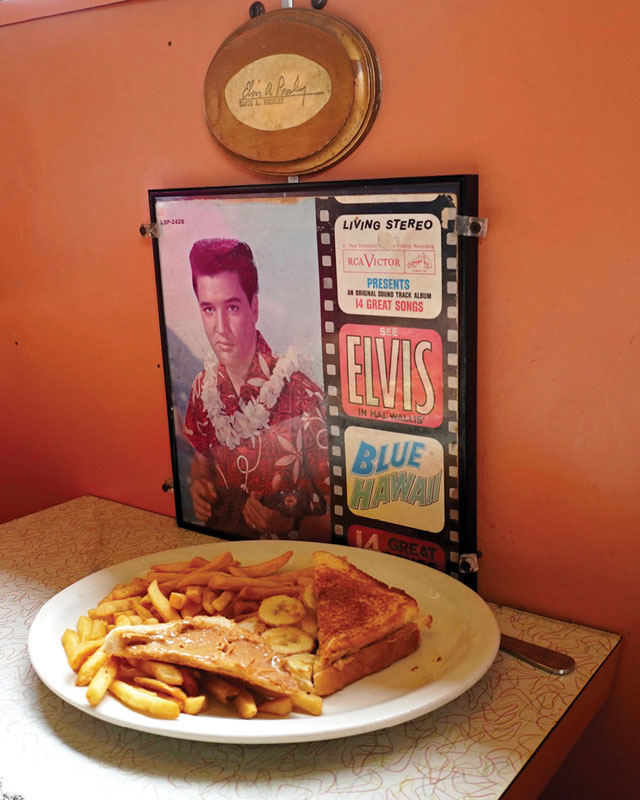

I am sitting at the Elvis Presley table in Memphis’s Arcade Restaurant. There are three ways to tell this is the Elvis Presley Table: 1) There is on the wall a small bronze plaque with Elvis’s signature engraved on it. 2) There is a framed copy of Presley’s album Blue Hawaii hanging below the plaque. 3) I am eating a peanut butter and banana sandwich with fries, Elvis’s most famous preferred delicacy. Lore has it that Elvis used to come in here, sit at this table, and order this sticky, slimy feast. It’s a story I am consciously not going to try and authenticate, because I just want it to be true.

Eight miles south of here, nearly 50 years after Presley’s death, the faithful still pay $80 a pop to walk through his home at Graceland, gasping at his wardrobe, marveling at his cars, humming the songs from his gold records.

I pay my tab and make my way down Beale Street to the broad Mississippi. From the rooftop patio bar at the new Hyatt Centric Beale Street, the view encompasses the river that carried the Music of America from the South to the North and back again. Somewhere, far below, someone is playing guitar on a sidewalk, the music fusing with that unseen artist’s dreams of finding music immortality.

Well, this is a good place to start looking.

Bill Newcott is film critic for The Saturday Evening Post, a Lowell Thomas Award-winning travel writer, and a three-time International Regional Magazine Association Writer of the Year.

This article is featured in the May/June 2023 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Great article. The article is meaningful

An insightful newsletter very educative entertaining and bold. Keep up the good work.

This is great content. For someone who grew up in the 50-60s America as an amateur musician, thus brings back so many memories.